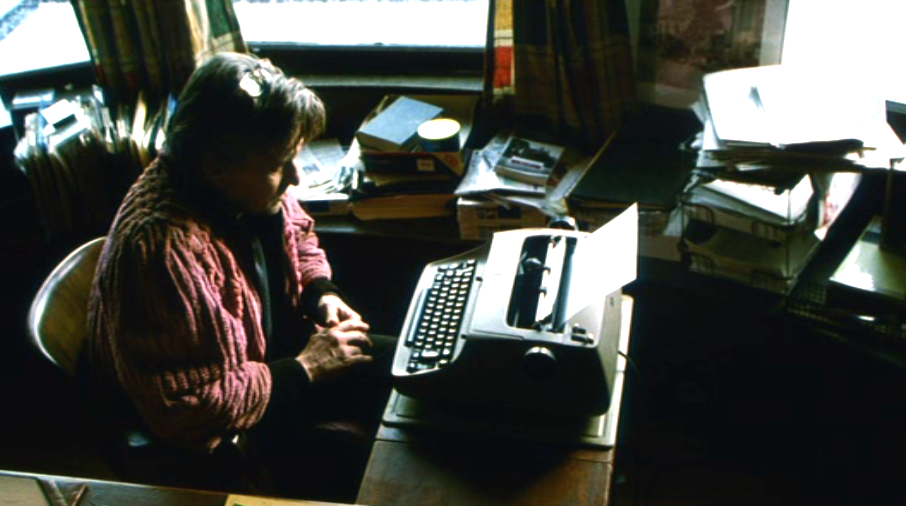

Underwood

«On the desktop there was an old manual Underwood with a piece of paper rolled into the carriage, a paragraph arrested in midphrase, and beside the typewriter a neat pile of paper, the uppermost sheet half covered in single-spaced text.»

«On the desktop there was an old manual Underwood with a piece of paper rolled into the carriage, a paragraph arrested in midphrase, and beside the typewriter a neat pile of paper, the uppermost sheet half covered in single-spaced text.»

Embarras de richesse

The more I think and write about Michael Chabon’s wonderful novel Wonder Boys and the movie by the same title, the more I feel infected and, for that matter, inflicted by his protagonist’s embarras de richesse – flooded with grandiose ideas, trenchant quotes and highfalutin intentions. «The only part of my world that carried on, inalterable and permanent, was Wonder Boys. I had the depressing thought, certainly not for the first time, that my novel might well survive me unfinished», says I-Narrator Grady Tripp.

But unlike him I am determined to gain the upper hand. After all, it is Michael Chabon himself who (supposedly) said: «You need three things to become a successful novelist: talent, luck and discipline. Discipline is the one element of those three things that you can control, and so that is the one that you have to focus on controlling, and you just have to hope and trust in the other two.» And, luckily, I am not working on a novel – this time.

Siehe auch den Beitrag «Verwirrung durch Überfülle».

Gebrochene Gebote #3 – Finger weg von Klischees!

Was soll man über Klischees sagen, das nicht schon tausendfach gesagt wurde? Am besten wir machen einen weiten Bogen um sie, meiden sie wie die Pest und lassen ein für allemal die Hände davon, bevor wir uns noch die Finger verbrennen. Natürlich ist das leichter gesagt als getan. Guter Rat ist also teuer. Doch last but not least hat eben alles immer zwei Seiten, nicht nur die berühmte Medaille.

Klischees können zwar ins Auge gehen, aber zum Glück haben wir ein lachendes und ein weinendes. Deshalb Schwamm drüber. Drücken wir ein Auge zu. Es ist ja noch nicht aller Tage Abend, und man muss auch mal fünf gerade sein lassen. Wie heisst es so schön? Eine Hand wäscht die andere, man darf sich nur nicht einseifen lassen.

Zitate übers Schreiben #2

Zitate übers Schreiben #1